Weather and Mississippi River Grain Transportation Impacts

Summary

Understanding the relationship between weather conditions, river levels, and grain transportation on the Mississippi River is critical for managing grain trading risk and optimizing logistics. This analysis highlights how fluctuations in gage height at St. Louis, driven by upstream precipitation and other weather variables, directly impact crop shipping volumes through Mississippi Lock 27.

Using advanced statistical techniques, including cross-correlation analysis, principal component analysis (PCA), and random forest modeling, the analysis demonstrates that weather-driven gage height changes significantly influence shipping capacity and costs, especially during critical trading months. A 21-day prediction model, leveraging CropProphet’s digital weather data feed, offers actionable insights to forecast river levels and mitigate transportation disruptions.

Grain traders can use CropProphet data to understand these river height/grain flow dynamics to anticipate logistical challenges and refine market strategies, especially during periods of extreme dry conditions across the Midwest.

In another detailed analysis, we explore how fluctuating Mississippi River water levels impact grain shipping efficiency, offering insights into the logistical challenges posed by both high and low river stages—read the full blog post here.

MS River Levels and Grain Transportation: Introduction

The agricultural market heavily depends on the volume of crops transported along the Mississippi River, with fluctuations in gage height—primarily driven by meteorological conditions—directly impacting shipping capacity. As approximately 60% of U.S. grain exports rely on the Mississippi River (Grumke, 2024), even slight changes in water levels can have significant grain shipping consequences.

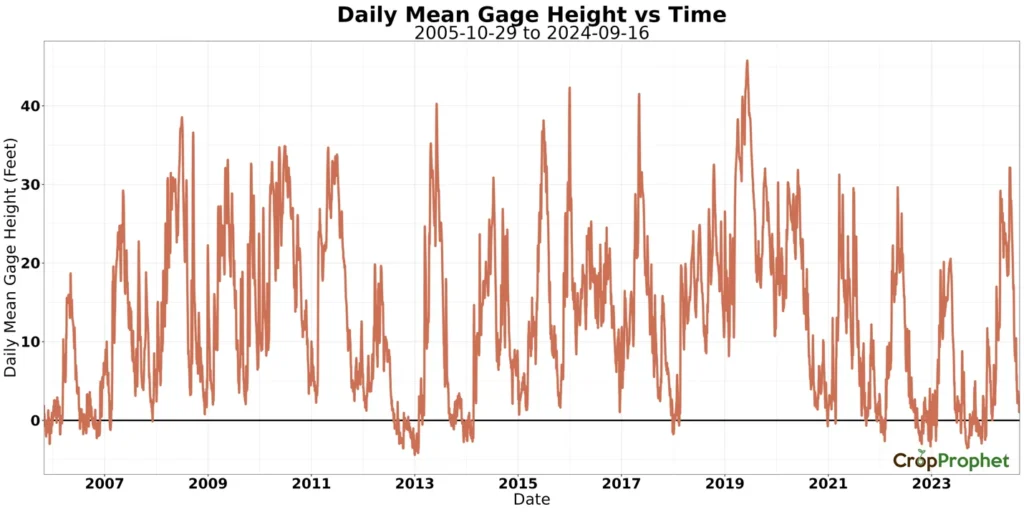

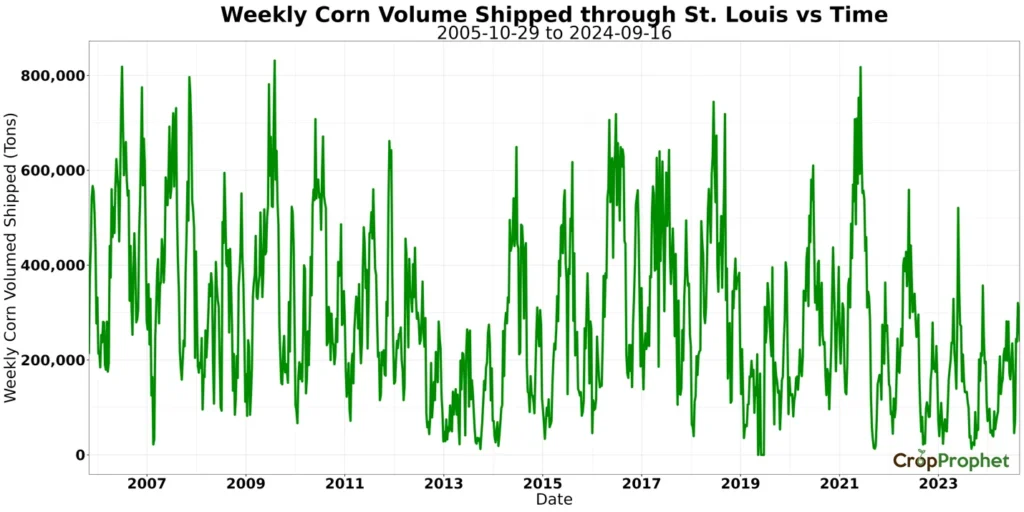

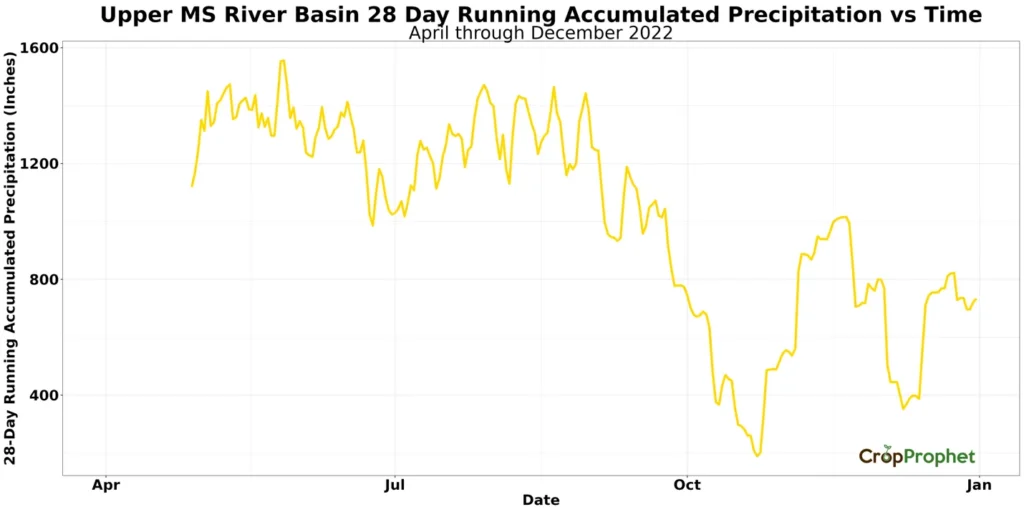

In the fall of 2022, particularly from September through October, the daily mean gage height dropped to unusually low levels, as depicted in Figure 2. This drop led to a marked decrease in grain tonnage passing through Mississippi Lock-27, as noted by Arita et al. (2022) and shown in Figure 3. Arita et al. (2022) explained, “When water levels are low, barges can’t carry as much grain because they risk running aground in shallower waters, and navigation issues arise as channels narrow. This reduced shipping capacity pushed costs higher. The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that the cost of shipping corn and soybeans via the Mississippi through the Gulf of Mexico surged by more than a third compared to 2023.” Figure 4 illustrates the dry conditions experienced in the fall of 2022, showing the 28-day accumulated precipitation in the Upper Mississippi River Basin over time.

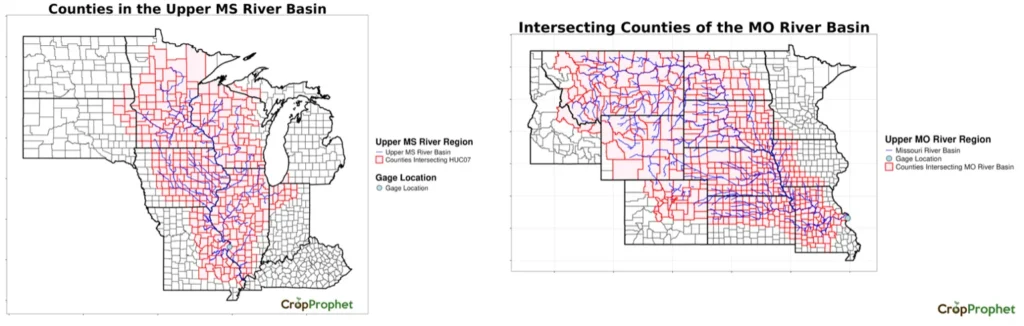

In this analysis, we dive into the critical relationship between river gage heights and the volume of corn and soybeans shipped through the Upper Mississippi and Missouri River Basins (Figure 1). With a focus on data from gage #0701 in St. Louis, Missouri (Figure 2), and crop shipping data from Lock 27 on Chouteau Island (Figure 3), we reveal the connection between changes in water levels and agricultural logistics. Using advanced tools like regression plots, lag correlation analysis, and real-time case studies, we uncover critical insights to help stakeholders manage risks and optimize crop shipments. All advanced tools used to find the key insights used weather variables such as precipitation (Figure 4), soil moisture, relative humidity, and maximum temperature. Additionally, based on this study and data from both basins, we suggest how to use CropProphet county-level, daily updated weather data to develop a gage height prediction model that forecasts the gage height in St. Louis, Missouri, up to 21 days in advance.

Mississippi River Drainage Basin Precipitation Data

CropProphet Modeler, our data feed of global grain market crop weather data feed provides access to US county-level historical precipitation data. The precipitation data used in this study was sourced from CropProphet Modeler. Modeler also provides access to CropProphet’s multi-year ensemble, median regression-based trend yield estimates.

Mississippi River Gage Height Data

The gage height data is sourced from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Dashboard using gage #0701 in St. Louis, Missouri. The data from this gage is downloaded and averaged daily (recorded initially every 30 minutes) from October 29, 2005, to September 7, 2024. The gage height is measured in feet.

Mississippi River Crop Volume Shipping Data

This analysis obtains the crop volume shipping data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) downbound barge grain movements dataset, which is updated weekly. This dataset provides weekly information on the amount (in tons), location, and type of grain transported by barge through three key points: (1) the final lock on the Mississippi River, Mississippi Locks 27 (referred to as “Miss Locks 27” in the dataset), capturing downbound traffic from the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers; (2) the final lock on the Ohio River, Olmsted Locks and Dam (referred to as “Ohio Olmstead” in the dataset), capturing traffic from the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers; and (3) the final lock on the Arkansas River, Arkansas River Lock and Dam 1 (referred to as “Ark Lock 1” in the dataset). This analysis focuses on Mississippi Lock 27, located in St. Louis, MO, as it captures downbound traffic from both the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. The data for crop volume shipped spans from October 29, 2005, to September 7, 2024.

Mississippi River Weather Impact Analysis Methods

This study analyzes the Upper Mississippi and Missouri River Basins to assess how gage height impacts crop transport through MS Lock 27. First, this study uses Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing or LOESS to visualize the relationship between weekly average gage height and normalized weekly tonnage of corn and soybean shipments, smoothing the data with 5-foot gage height intervals.

Next, we examine how 30- and 60-day precipitation accumulation influences gage height and corn shipping volumes. A cross-correlation analysis explores how deviations in precipitation, soil moisture, relative humidity, and max temperature (over rolling periods of 1 to 42 days) affect gage height. This analysis reveals key patterns across both river basins.

To predict gage height up to 21 days ahead, this analysis identifies the most impactful rolling periods (14, 21, and 28 days) and used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to minimize multicollinearity among weather variables. We then built a random forest model for each period to forecast gage height, evaluating the importance of each weather variable based on mean squared error and node purity.

The final model’s performance was measured using R-squared values, indicating which weather variables most effectively predicts gage height.

Cross-Correlation Regression

The CCR (Cross-Correlation Regression) approach helps to gain a better understanding of how precipitation, soil moisture, relative humidity, and maximum temperature influence gage height at different time scales. CCR is a method used to explore the relationship between two-time series, allowing visualization of the strength of the relationship between one series (such as a weather variable) and another (gage height) at different time lags. This approach is particularly useful when changes in one variable is expected to have a delayed impact on the second variable. Combining cross-correlation with regression accounts for the magnitude and timing (lag) of the influence of various weather variables on gage height.

Principal Component Analysis

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a statistical method that eliminates multicollinearity among the weather variables before constructing the gage height prediction model. Correlated variables can introduce redundant information which negative impacts model development during the training process. Removing multicollinearity using PCA helps create a more efficient prediction model, reducing the chances of downplaying the importance of individual variables and avoiding unnecessary noise. PCA preserves as much variability information as possible by transforming the original variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables known as principal components (PCs). These PCs are arranged in order of importance, with the first few explaining most of the variation in the dataset (for example, the first two PCs together might explain 55% of the total variance of the original data).

PCA is applied to N-day rolling accumulated precipitation and averaged daily maximum temperatures, daily relative humidity, and daily soil moisture aggregated for the counties in each of the Upper Mississippi and Missouri river basins. The PCA is applied across eight variables comprising the four variables in each basin. The accumulation/averaging period is 14, 21, and 28 days, as informed by the CCR analysis.

Random Forest Model

We use the time series associated with each principal component as the predictor for the river height forecast model. Random forest regression is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the average prediction of all the trees. In this analysis, each tree makes a prediction based on a random subset of the weather variables, and the final gage height prediction is the average of all the individual tree predictions.

A random forest begins by creating a decision tree and then builds many more decision trees based on random subsets of the data. Once all the trees are constructed, they each make their predictions. The final prediction is the average prediction made by each of the trees. Random forests are powerful and flexible, making them well-suited for handling a variety of data types and complex relationships.

Weather Impact Analysis: Mississippi River Levels and Grain Transportation

Mississippi River and Grain Shipments at St. Louis

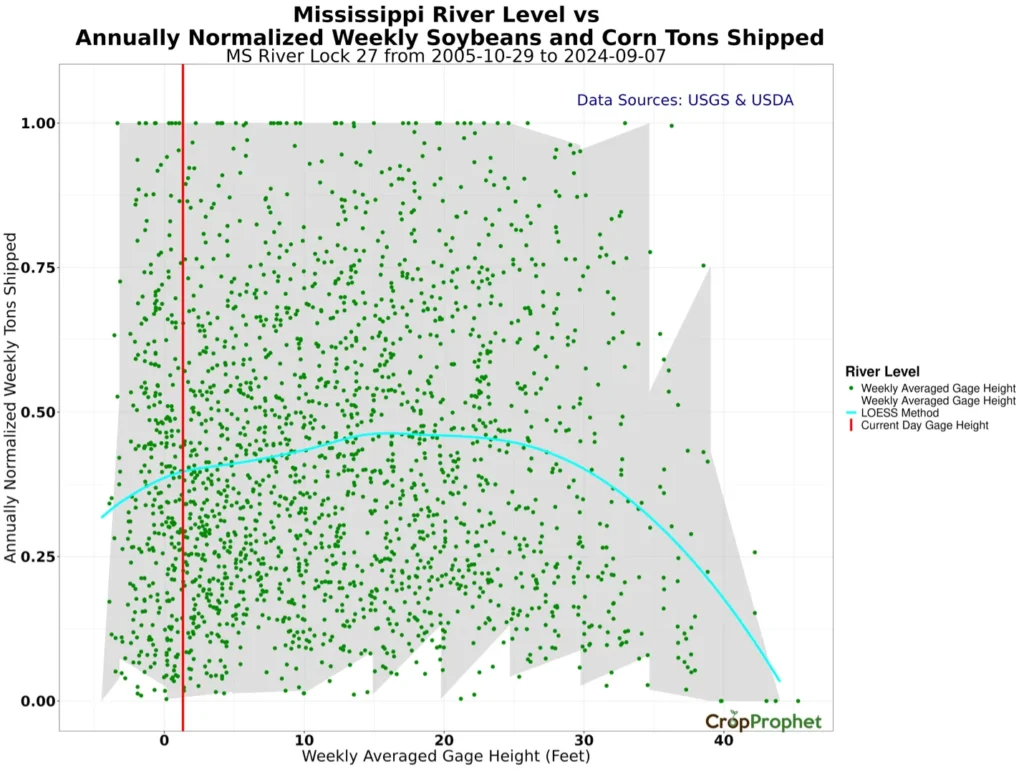

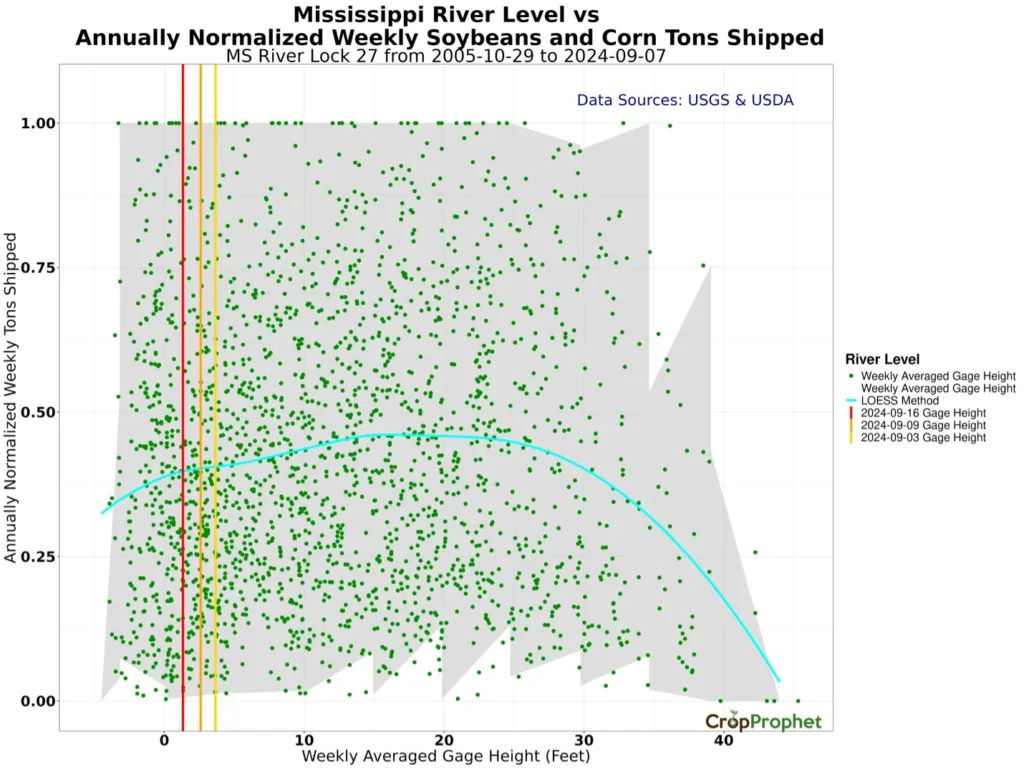

To assess the impact of Mississippi River heights at St. Louis on the volume of grain crops shipped and exported through the Upper Mississippi River Basin, this analysis plots the weekly average gage height alongside the annually normalized by weekly tonnage of soybeans and corn shipped. Figure 5 depicts the gage height for the current day, September 16, 2024. LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) was used to create a smooth line through the scatterplot by fitting multiple regressions within localized subsets of the data, specifically using bins of 5 feet for gage height.

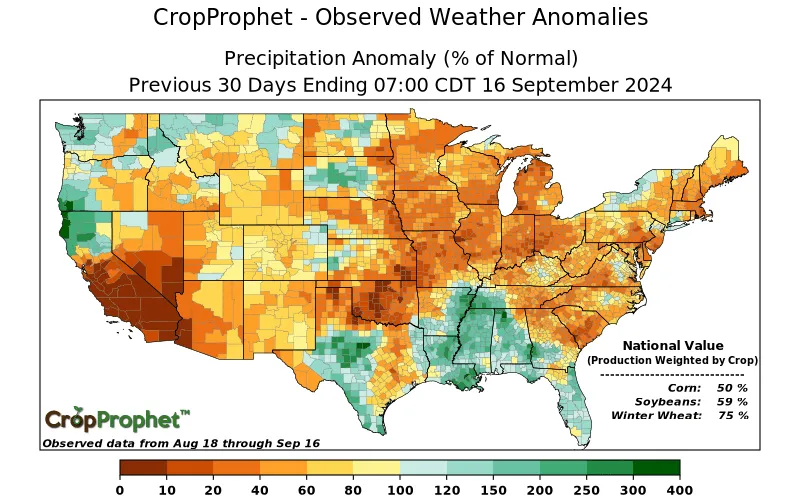

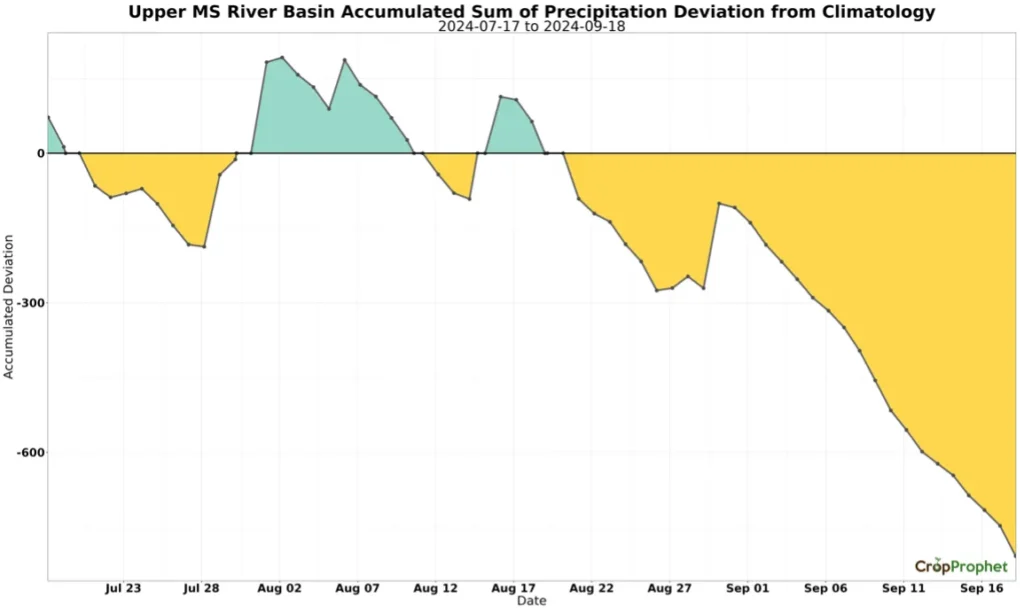

At both the beginning (near and less than 0 feet) and end (more than 30 feet) of the plot, the regression shows a downward trend indicating an impact on the grain volume at even slightly below normal river levels. From early to mid-September in 2024, the Upper Mississippi River Basin experienced significant dryness, as illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7. The prolonged dry conditions over the 60 days leading up to September 16, 2024, caused the gage height to continue its decline, represented by the solid vertical line shifting left in Figure 8. As this line moves left over time, the annual normalized tonnage shipped decreases from around 0.9 normalized corn tons shipped in the middle of August 2024 to around 0.3 normalized corn tons shipped in the middle of September 2024.

St. Louis Grain Shipment Volume – Seasonality

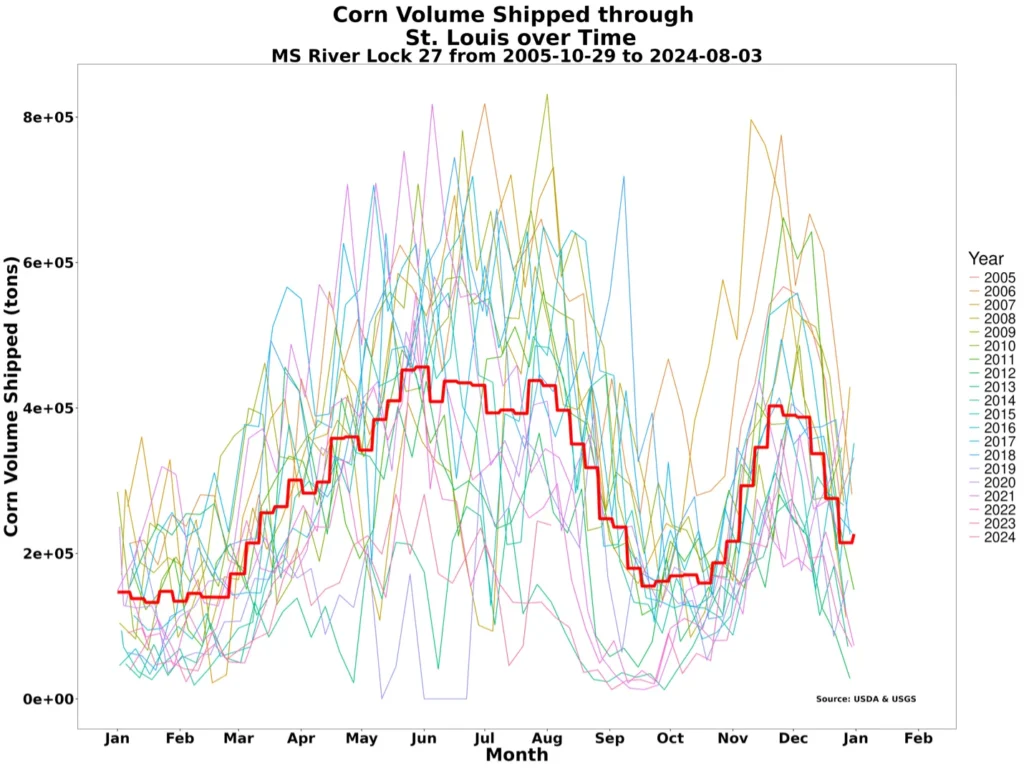

Figure 9 shows the corn shipment volumes through St. Louis, MO, for each year, along with the weekly average values across all years (in red). A clear seasonal pattern emerges. Corn shipments experience a lull from January to early March, followed by a significant rise. Shipments peak in June and remain steady through early August. After that, there’s a gradual decline, which accelerates as September draws near. Another dip occurs in October, but the volume substantially rebounds in December.

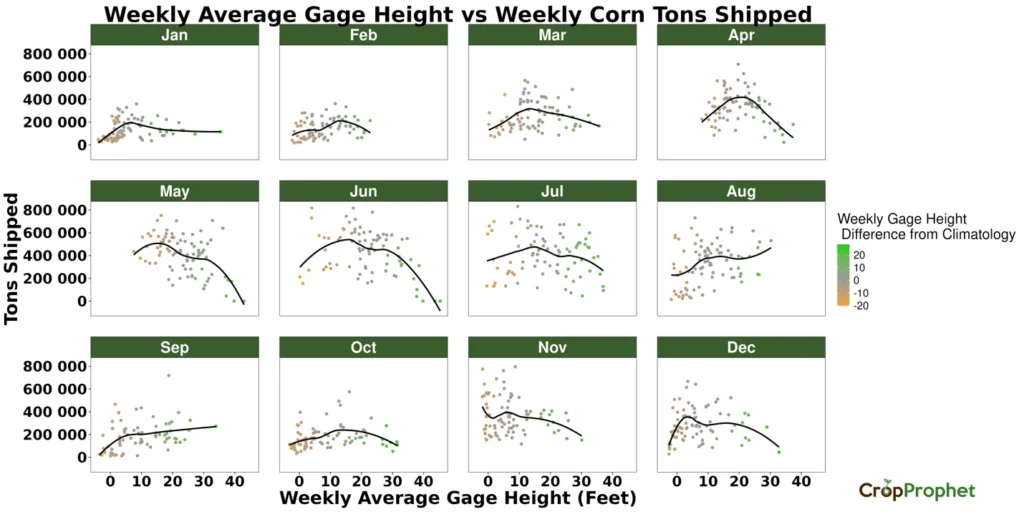

This analysis also explores the regression between weekly average gage height and the amount of corn shipped each week, as shown in Figure 10, while also considering monthly corn volumes. Analyzing the relationship between gage height and the volume of crops shipped along the Mississippi River offers several advantages, such as predicting transportation costs, optimizing supply chain efficiency, and providing valuable market and pricing insights. By focusing on key shipping months—May, June, July, and December—a distinct pattern emerges. This reveals that the lowest and highest weekly gage heights result in the smallest volumes of corn shipped. In contrast, when the gage height is close to average, the most significant corn shipments from the Upper Mississippi River Basin through St. Louis occurs.

Upper Mississippi River Drainage Basin Weather Variables vs. St. Louis Gage Height

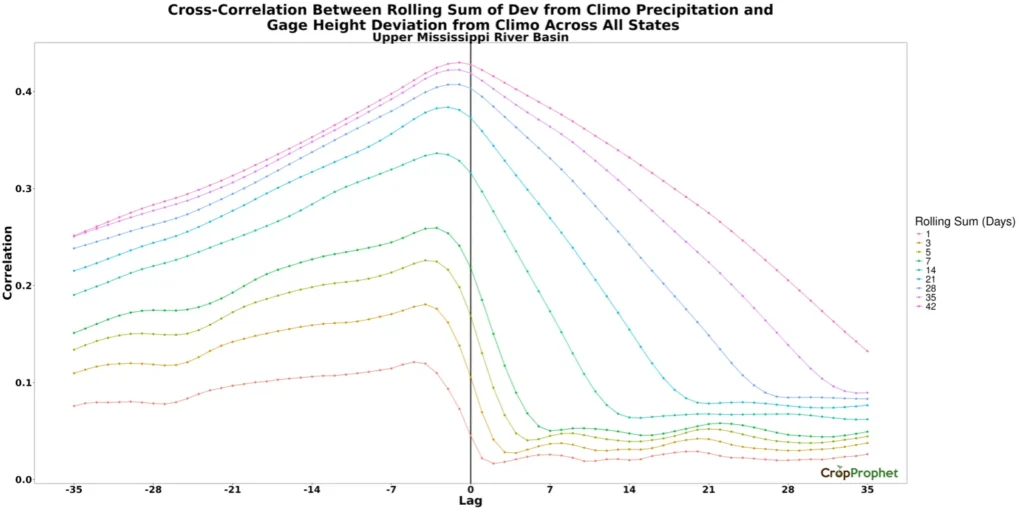

A cross-correlation regression analysis was performed to understand the influence of precipitation on river gage height. Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between the rolling sum deviation from climatology precipitation and gage height deviation from climatology across the Upper MS River Basin for rolling periods from 1 to 42 days. It focuses only on the counties within the Upper Mississippi River Basin. The analysis reveals that correlations peak at around a negative 1-day lag for rolling sums of 28, 35, and 42 days within the Upper Mississippi River Basin and a negative 3-day lag for rolling sums of 14 and 21 days. To add on, there is a significant jump in the average correlation from the 7-day rolling sum period to the 14-day rolling sum period.

The physical interpretation of this result suggests that precipitation and other weather variables in the Upper Mississippi River Basin have a delayed but significant impact on gage height in St. Louis. This is not unexpected, considering that a raindrop that falls in the Upper Mississippi River valley must flow through the streams and rivers over sometimes considerable distance to get to St. Louis. The 1-day accumulated precipitation correlation maximum at a 5-day lag indicates that precipitation changes in the basin lead to corresponding changes in gage height five days later at the shortest time scales. The lag of maximum correlations reduces to 1 day by the 42-day accumulation period because the accumulation reduces the short-term variability.

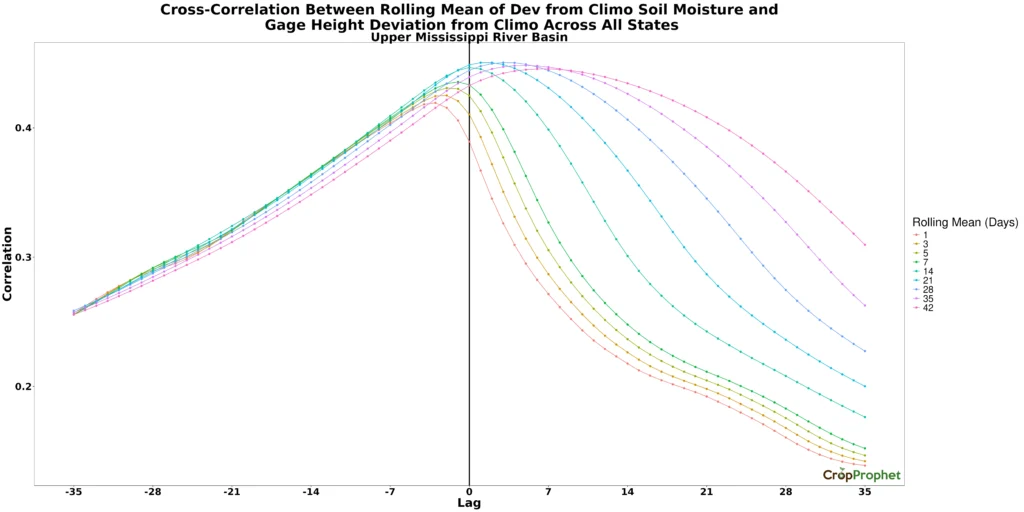

This study also employs a cross-correlation analysis involving additional weather variables, including soil moisture, relative humidity, and maximum temperature in the Upper Mississippi River Basin. Soil moisture is the 7-28 cm soil moisture measured in standard deviation units. The cross-correlation between the rolling mean of soil moisture deviation from climatology and gage height deviation from climatology is evaluated across all states considered in the analysis (Figure 12). Results show that the maximum average correlation exhibits a positive lag for over half of the rolling mean periods (notably at 14-, 21-, 28-, 35-, and 42-day rolling means).

A positive lag in soil moisture indicates that changes in soil moisture precede corresponding changes in gage height. This implies that an increase or decrease in soil moisture at a certain point is linked to a rise or fall in gage height a specific number of days later. Since precipitation initially increases soil moisture, it may take some time for runoff to accumulate, eventually leading to higher water levels at the river gage.

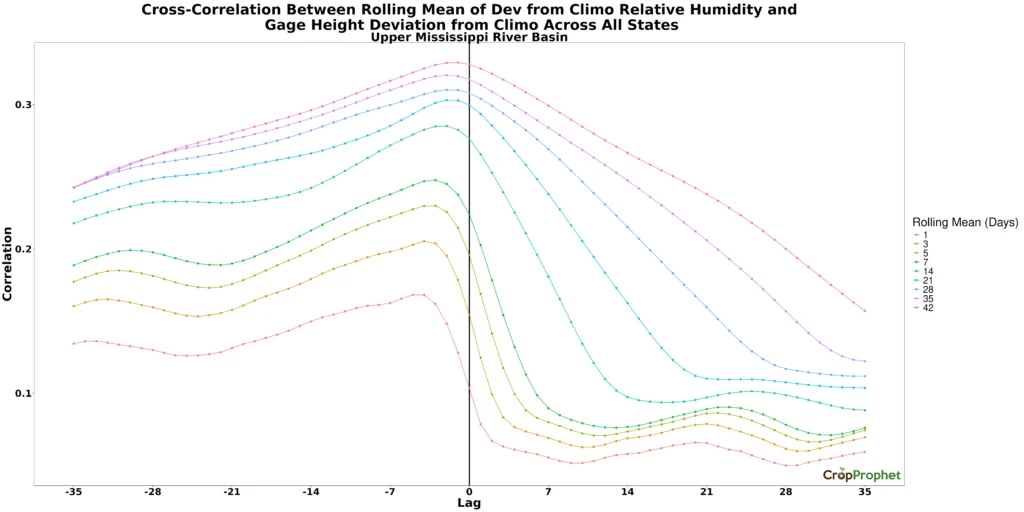

Figure 13 illustrates the cross-correlation between the rolling mean of relative humidity (RH) deviation from climatology and gage height deviation across all states for the Upper MS River Basin. The highest average correlation is associated with negative lag days for all rolling mean periods. In this context, negative lag suggests that past RH deviations (occurring before the gage height change) influence the gage height deviation from climatology.

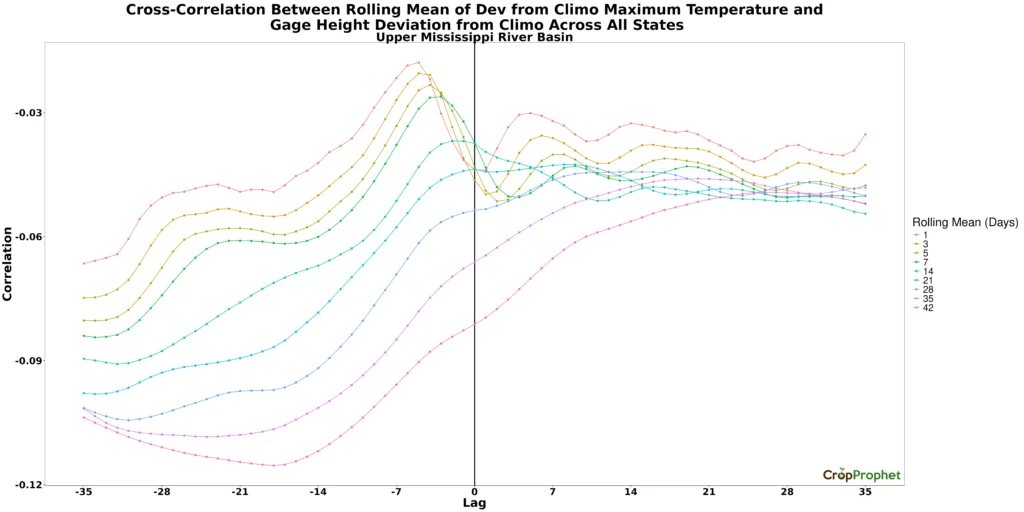

The final weather variable analyzed for its influence on gage height in St. Louis, MO, is maximum temperature. Figure 14 presents the cross-correlation between the rolling mean of maximum temperature (maximum temperature) deviation from climatology and gage height deviation from climatology across all states in the Upper MS River Basin. The analysis shows a slightly negative average correlation between maximum temperature deviation and gauge height deviation, with the strongest average correlation occurring at a negative lag. A negative correlation suggests that gage height tends to decrease when the maximum temperature increases. As maximum temperature increases, it likely drives processes such as increased evaporation and reduced runoff, leading to lower river levels and causing the gage height to drop. This explains why the negative correlation indicates that maximum temperature has an inverse effect on gage height in the days ahead.

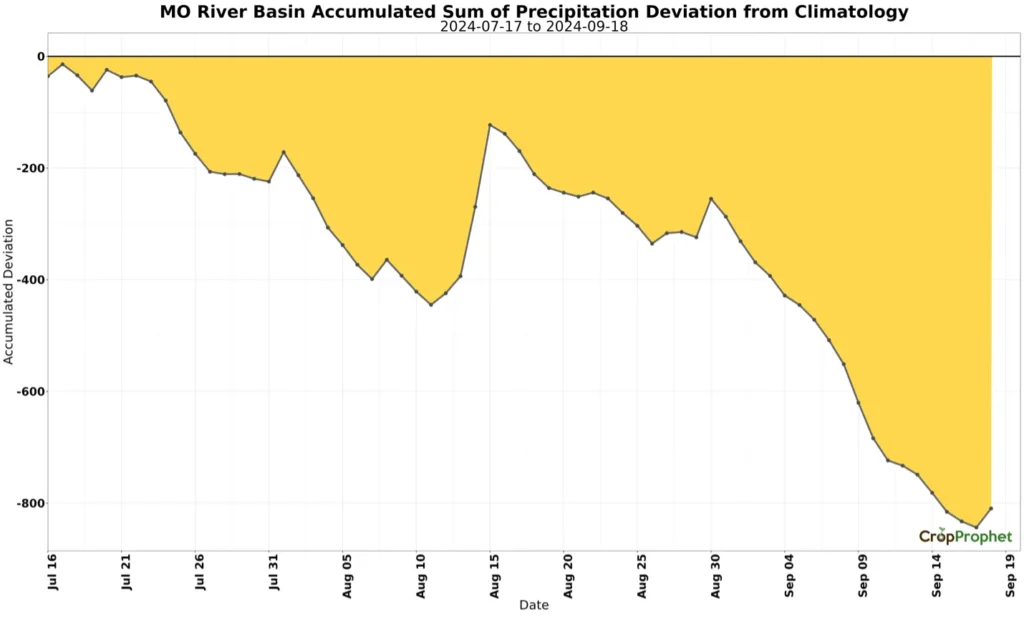

Missouri River Drain Basin and Mississippi River Gage Heights

The same analysis was applied to the Missouri River Basin. As shown in Figures 1 and 3, most of the Missouri River Basin experienced substantial dryness during the 60 days leading up to September 16, 2024. Figure 15 presents the accumulated sum of precipitation deviation from climatology observations starting from July 18, 2024, with model forecasts initialized on September 16, 2024. The analysis for the Missouri River Basin mirrors that of the Upper Mississippi River Basin, as both rivers flow into St. Louis, Missouri, and use the same port and lock system. Specifically, Figures 2, 5, and 7 are relevant to both basins. According to USDA data, the final lock on the Mississippi, known as Mississippi Locks 27 (“Miss Locks 27” in the dataset), captures downstream traffic from both the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.

Missouri River Drainage Basin Weather Variables vs. St. Louis Gage Height

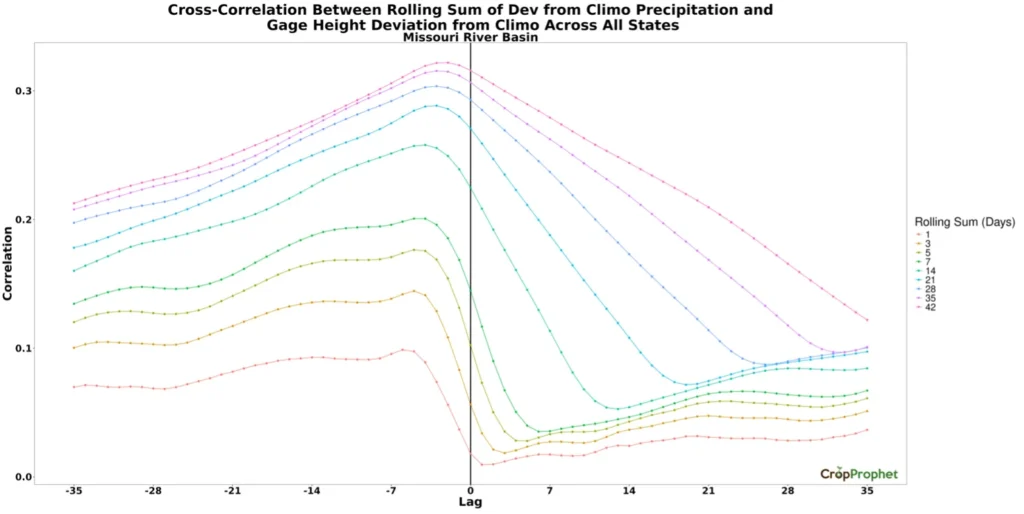

The cross-correlation analysis for the Missouri River Basin shows similar patterns across states but with some variations (Figures 15 and 16). Figure 16 illustrates the cross-correlation between the rolling sum deviation from climatology precipitation and gage height deviation from climatology, focusing on the Missouri River Basin. The analysis reveals that correlations peak at around a negative 2-day lag for rolling sums of 21, 28, 35, and 42 days within the Missouri River Basin and a negative 4-day lag for rolling sums of 14 days. Additionally, there is a significant jump in average correlation from the 7-day rolling sum period to the 14-day rolling sum period.

For instance, the peak at a negative 2-day lag for the longer rolling sums (21, 28, 35, 42 days) means that significant, accumulated precipitation in these periods has its greatest impact on gage height just before the actual measurements, likely reflecting the time it takes for runoff and drainage to flow downstream to St. Louis. The slightly longer negative lag of 4 days for shorter rolling sums (21 days) suggests gage height responds more slowly to shorter-term precipitation.

As with the Upper Mississippi River Basin analysis, this section applies a cross-correlation approach to additional weather variables in the Missouri River Basin. The variables analyzed for this cross-correlation include soil moisture, relative humidity, and maximum temperature.

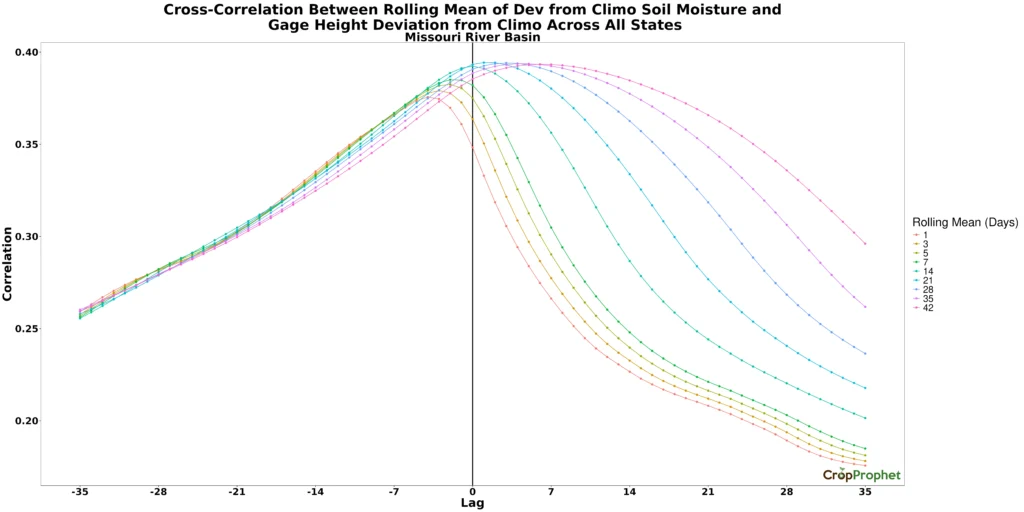

Figure 17 presents the cross-correlation between the rolling mean of soil moisture deviation from climatology and gage height deviation across all Missouri River Basin states. Similar to Figure 12, this graphic shows positive rolling mean lags. A positive lag in soil moisture indicates that changes in soil moisture precede the corresponding changes in gage height. This suggests that an increase or decrease in soil moisture at a certain point is associated with a rise or fall in gage height a specific number of days later. Since precipitation initially increases soil moisture, it may take time for the runoff to accumulate and subsequently raise water levels at the river gage.

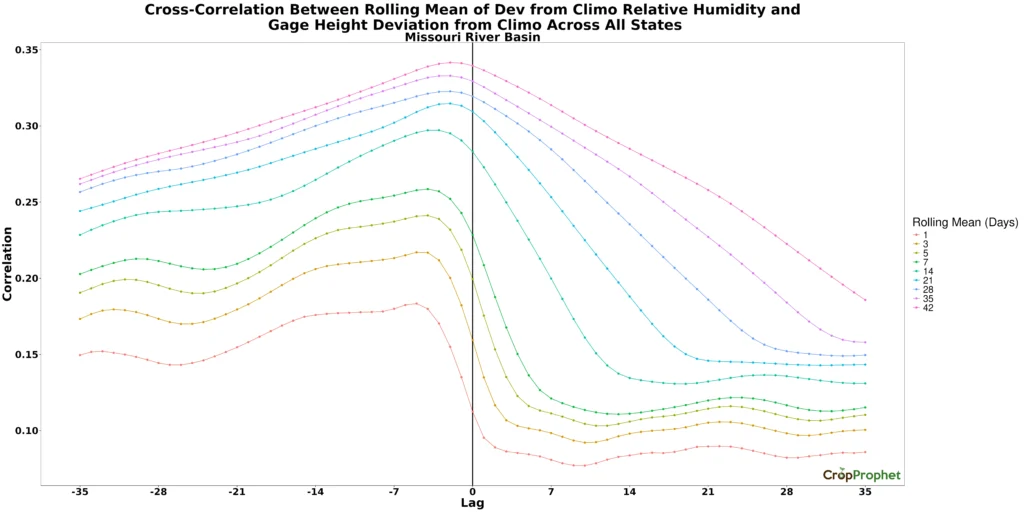

The next weather variable analyzed using the cross-correlation approach in the Missouri River Basin is relative humidity (Figure 18). A similar pattern is observed in the Missouri River Basin compared to the Upper Mississippi River Basin graphic (Figure 13). Focusing on RH, a positive average correlation is evident for all rolling mean periods, with the highest average correlation occurring at a specific negative lag day. A negative lag indicates that gage height deviation from climatology is correlated with past deviations in relative humidity (before the observed change in gage height).

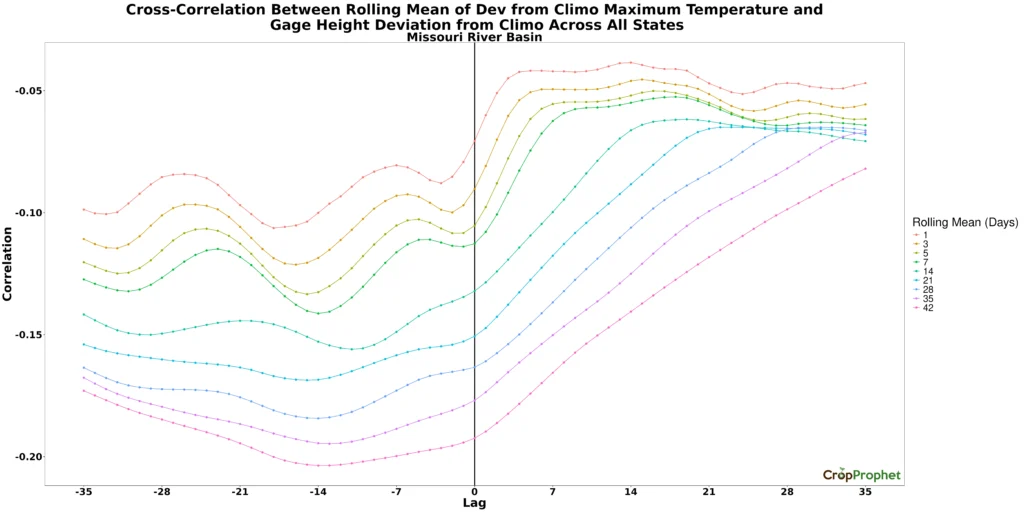

Maximum temperature is the final weather variable that this study analyzes using the cross-correlation approach for the Missouri River Basin (Figure 19). A similar pattern is observed here when compared to the maximum temperature graphic for the Upper Mississippi River Basin (Figure 14). A negative average correlation indicates that gage height tends to increase as maximum temperature decreases. As maximum temperature decreases, it likely drives processes such as reduced evaporation and increased runoff, leading to higher river levels, causing the gage height to increase. This explains why the correlation is negative which indicates that maximum temperature has an inverse effect on gage height in the days ahead.

St. Louis Mississippi River Gage Height Prediction Model – Principal Component Analysis:

We combine the objective findings above to perform a PCA to explore the possibility of predicting gage #0701 height up to 21 days in advance. We considered 14-, 21-, and 28-day rolling periods for each weather variable from both basins. The primary goal was to identify which rolling sum or mean period explained the most variance in gage height and to determine which weather variables (such as precipitation, soil moisture, relative humidity, and max temperature) contributed most to the variance within each principal component (PC). By including PCA in the model-building process, we were able to reduce multicollinearity among the weather variables. Since correlated variables can introduce redundant information, removing multicollinearity made the model more efficient, minimizing the risk of diluting the importance of key variables and reducing unnecessary noise.

The orthogonal vectors were extracted for each rolling period, as shown in Table 1. Each principal component (PC) is a vector representing a combination of the original weather variables. The direction of each principal component indicates how each of the analysis variables varies together. Table 1 highlights the pr from the 14-day, 21-day, and 28-day models, indicating the contribution of each variable to each PC. The values in the table show how much each weather variable contributes to a specific PC. Positive or negative signs indicate the direction of influence, while larger absolute values reflect a greater contribution of that variable to the PC.

(a)

(b)

(c)

The PCA also summarizes the variance explained by each principal component (PC), as illustrated in Table 2. In Table 2a, PC1 and PC2, the first two principal components of the 14-day model, together explain approximately 51% of the total variance. The 21-day and 28-day models show similar values for the first two PCs, where they account for approximately 53% and 54% of the total variance explained, respectively.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Mississippi River Gage Height Prediction Model – Random Forest Model

This analysis utilizes the PCAs for each basin’s rolling sum/mean periods to develop a random forest model for predicting gage height across different rolling periods (i.e., 14, 21, and 28 days). Three random forest models were created: a 14-day, 21-day, and 28-day models.

After training each random forest model, the importance of each principal component (PC) was assessed by calculating the percent increase in MSE and the increase in node purity (as shown in Table 3). When examining the percent increase in MSE, PC1 is the most significant across all models, indicating its substantial contribution to increasing prediction accuracy. A higher percentage increase in MSE signifies that the variable is more crucial for making accurate predictions.

The 14-day model has the highest percent increase in MSE, at approximately 149%, with the values decreasing as the forecast period increases. Conversely, for the increase in node purity, the 28-day model has the highest value (148,919.910), while the 14-day model has the lowest. A higher value for the increase in node purity indicates that the variable contributes more to generating pure or well-split decision nodes in the forest.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Next, this analysis calculates the R-squared values for each model, as shown in Table 4. While all models explain the majority of the variance, Table 4 indicates that the 28-day model has the highest R-squared value, at 0.982.

This result suggests CropProphet county-level digital data can be used to create a very accurate Mississippi River height forecasting solution at any of the time periods tested.

Conclusion:

Crop shipments through St. Louis, Missouri, are heavily influenced by gage height, directly tied to precipitation levels. As rainfall accumulates or diminishes, gage heights rise and fall accordingly (Figure 5). When water levels are too low or too high, it significantly impacts the ability to transport crops from the Upper Mississippi River Basin. This analysis uses an example from early to mid-September 2024 to illustrate the impact of extreme drought conditions on gage height and crop shipping volumes. From July 18 to September 16, 2024, the Upper Mississippi River Basin experienced severe dryness, leading to lower gage heights and reduced crop shipments through St. Louis. While this period typically sees a peak in shipments (Figure 9), the volume of corn and soybeans was notably reduced due to these lower water levels.

The same trends were observed in the Missouri River Basin analysis. Crops shipped through St. Louis are similarly affected by gage height, which fluctuates with precipitation levels. In the example from mid-September 2024, prolonged dry conditions from July 18 to September 16 caused lower gage heights, restricting crop shipments through the region. Although this is typically a high-shipment period, the lower water levels resulted in reduced volumes of corn and soybeans shipped.

Additionally, the analysis examines the correlation between precipitation and gage height using a cross-correlation approach. The strongest average correlations were observed during the 14, 21-, 28-, 35-, and 42-day periods across both basins, demonstrating a clear relationship between the rolling sum of precipitation deviations from climatology and gage height deviations. Weather variables, such as soil moisture, relative humidity, and maximum temperature, were also analyzed through cross-correlation for each basin, showing similar patterns.

Lastly, three models (14-day, 21-day, and 28-day) were developed to predict gage height in future periods. Based on the findings from this PCA analysis, the 21-day model was chosen as the final model for predicting gage height at gage #0701. This model proved effective in predicting gage height and explaining much of the variance. We selected the 21-day model because it provides statistically similar accuracy to the other models while offering a 21-day forecast window, which is sufficient warning time for grain traders.

Looking ahead, further analyses will explore how precipitation, gage height, and shipping volumes interact and how these factors influence crop futures, particularly for corn and soybeans. Furthermore, a Mississippi River-level forecast system may be implemented.

Works Cited:

Arita, S., V. Breneman, S. Meyer, and B. Rippey. “Low Mississippi River Barge Disruptions: Effects on Grain Barge Movement, Basis, and Fertilizer Prices.” farmdoc daily 12(164), Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 2, 2022.

Grumke, K. (2024, September 23). Low Mississippi River levels are again making it more expensive to transport crops in the Midwest – IPM newsroom. Illinois Newsroom. https://ipmnewsroom.org/low-mississippi-river-levels-are-again-making-it-more-expensive-to-transport-crops-in-the-midwest/