Mississippi River Water Levels: Impact on Soybean and Corn Barge Shipping Efficiency

Summary: Navigating River Depth Challenges in Grain Shipping

In each of the past three years (2022, 2023, and 2024) the Mississippi River was low enough to engender grain shipment concerns in grain trading markers. This analysis is motivated by Mike Steenhoek’s (executive director, Soy Transportation Coalition) quote stating, “Every foot of reduced water depth or draft equates to loading 7,000 fewer bushels of soybeans on an individual barge.” Using historical data from 2005 to 2024, we explore how deviations from the critical gage height—0.36 feet—affect grain shipping volumes, focusing on corn and soybeans.

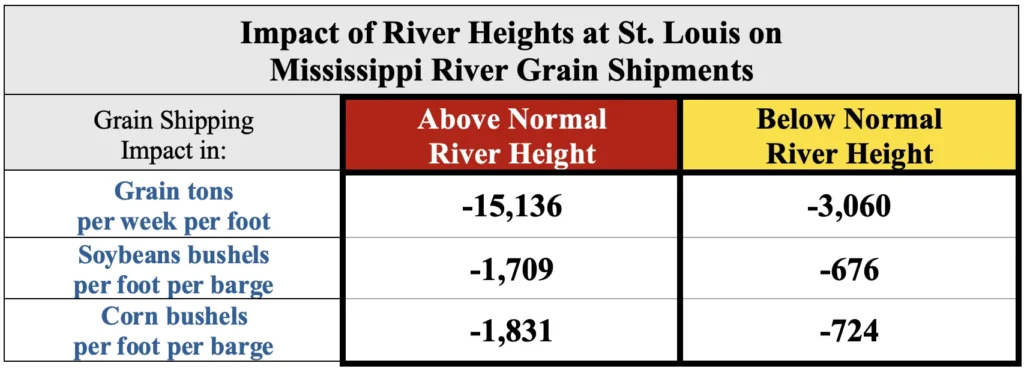

Key findings indicate that both high and low river levels reduce grain shipping capacity, but high water levels have a more significant impact. Specifically:

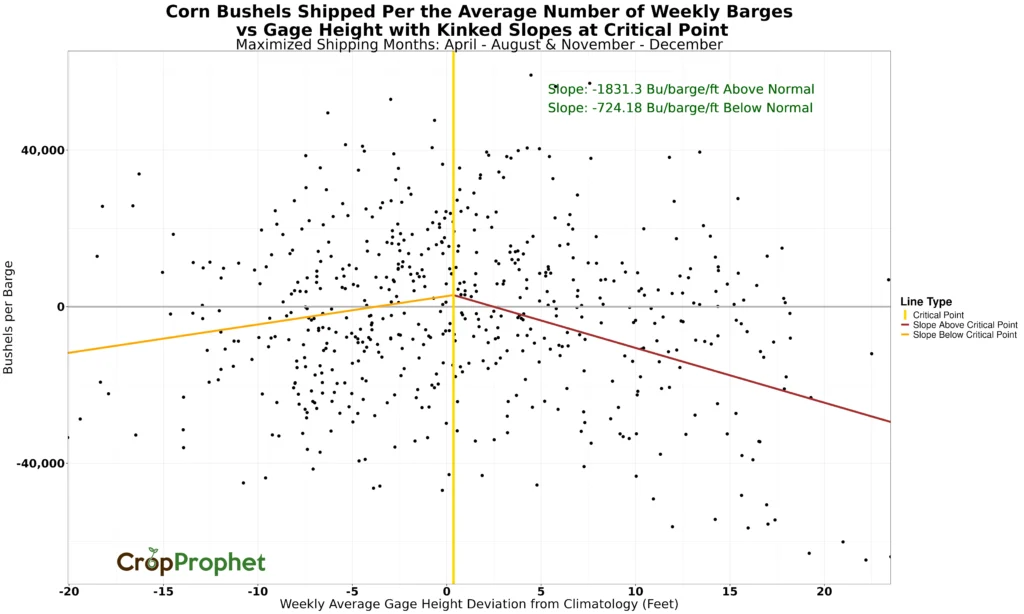

- Above-normal river heights result in steeper declines, with shipping reductions of 1,709 soybean bushels and 1,831 corn bushels per barge per foot.

- Below-normal river heights show less severe impacts, with reductions of 676 soybean bushels and 724 corn bushels per barge per foot.

The analysis also identifies asymmetry in the effects, as high water levels introduce greater operational challenges compared to low water levels.

Table 1 summarizes these findings, quantifying the rate of change in shipping efficiency in relation to gage height deviations. These results diverge from the quote’s estimated 7,000-bushel reduction, emphasizing the nuanced relationship between water levels and Mississippi River grain shipping capacity.

Impact of River Heights at St. Louis on Mississippi River Grain Shipments

Table 1. Summary of the calculated impacts above and below the critical point for Figures 6, 7-a, and 7-b. The table highlights the impact of deviations from the critical point on Mississippi River grain shipping capacity, with separate analyses for grain tons (Figure 6), soybean bushels (Figure 7-a), and corn bushels (Figure 7-b). The slopes quantify the rate of change in shipping efficiency with gage height deviations from climatology.

Additionally, we conducted a separate analysis of the weather’s influence on Mississippi River grain transport. Tools like CropProphet offer valuable precipitation monitoring at the county level, providing early warnings for potential disruptions and enhancing supply chain resilience

Introduction

An insightful article from the AgWeb Farm Journal highlights a critical logistical challenge in soybean transport via the Mississippi River, as explained by Mike Steenhoek. Steenhoek observes, “Every foot of reduced water depth or draft equates to loading 7,000 fewer bushels of soybeans on an individual barge.” He further explains, “Overall reductions range from 10% to 15% on the modest end, reaching as much as 30% to 40%, which is a substantial impact.” At CropProphet, we endeavor to provide objective weather-based grain market information based on available data. Mr. Steenhoek’s quote motivated us to verify these striking figures to understand the impact of precipitation on grain shipment volumes. So, we examine available data to uncover the broader implications of fluctuating river levels on agricultural transport.

Reduced water depths present clear challenges, but significant water depth changes can also disrupt barge efficiency and barge-based grain shipping volume. This analysis investigates the relationship between variations in Mississippi River water levels—whether high or low—and the impact on river-based grain shipping volumes. Mr. Steenhoek’s quote focuses the analysis on corn and soybeans while we evaluate what these shifts mean for the agricultural industry as a whole.

Data

Mississippi River Gage Height Data

The gage height data is sourced from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Dashboard using gage #0701 in St. Louis, Missouri. The data from this gage is downloaded and averaged daily (recorded initially every 30 minutes) from October 29, 2005, to September 7, 2024. The gage height is measured in feet.

Mississippi River Crop Volume Shipping Data

This analysis uses the crop volume shipping data provided by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) downbound barge grain movements dataset, which is updated weekly. This dataset provides weekly information on the amount (in tons), location, and type of grain transported by barge through three key points: (1) the final lock on the Mississippi River, Mississippi Locks 27 (referred to as “Miss Locks 27” in the dataset), capturing downbound traffic from the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers; (2) the final lock on the Ohio River, Olmsted Locks and Dam (referred to as “Ohio Olmstead” in the dataset), capturing traffic from the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers; and (3) the final lock on the Arkansas River, Arkansas River Lock and Dam 1 (referred to as “Ark Lock 1” in the dataset). This analysis focuses on Mississippi Lock 27, located in St. Louis, MO, as it captures downbound traffic from both the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. The data for crop volume shipped spans from October 29, 2005, to September 7, 2024.

Mississippi River Upbound and Downbound Loaded and Empty Barge Movements (Count) Data

This analysis incorporates barge movement data over time from the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) upbound and downbound loaded and empty barge movements dataset, which is updated weekly. The dataset provides weekly details on the number, location, direction, and type of barges transiting three major locations:

- Mississippi River Locks 27 (“Miss Locks 27”)—the final lock on the Mississippi River, located in St. Louis, Missouri.

- Olmsted Locks and Dam—the final lock on the Ohio River.

- Arkansas River Lock and Dam 1 (“Ark Lock 1”)—the final lock on the Arkansas River.

For this analysis, Mississippi Locks 27 was selected, as it captures downbound traffic from the Upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. This lock also aligns with the crop shipping volume dataset used. The focus is on downbound barge movements and the “Grain” category, which includes corn and soybeans.

Climatology

Climatology, in this context, represents the weekly average or normal value, calculated based on historical data. For instance, to determine climatology for a specific week, we calculate the mean of all weekly average gage heights, or the weekly tons or bushels shipped for that same week across the entire dataset. Essentially, climatology provides a baseline or “normal” for comparison.

After establishing the climatology, we calculate the deviation from it. This deviation indicates how much each weekly value differs from the established normal or climatology. In simpler terms, it measures the variation of the current weekly value relative to the expected average for that week.

Mississippi River Level Grain Shipment Impact: Analysis

Grain Tons Shipped and Gage Height

Building on the original quote, “Every foot of reduced water depth or draft is the equivalent of loading 7,000 fewer bushels of soybeans on an individual barge,” the analysis employs a scatterplot to illustrate the relationship between the combined weekly corn and soybean tons shipped deviation and the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology (measured in feet). To align the transportation data, which is reported weekly, we calculate weekly averages from the daily river gage height data.

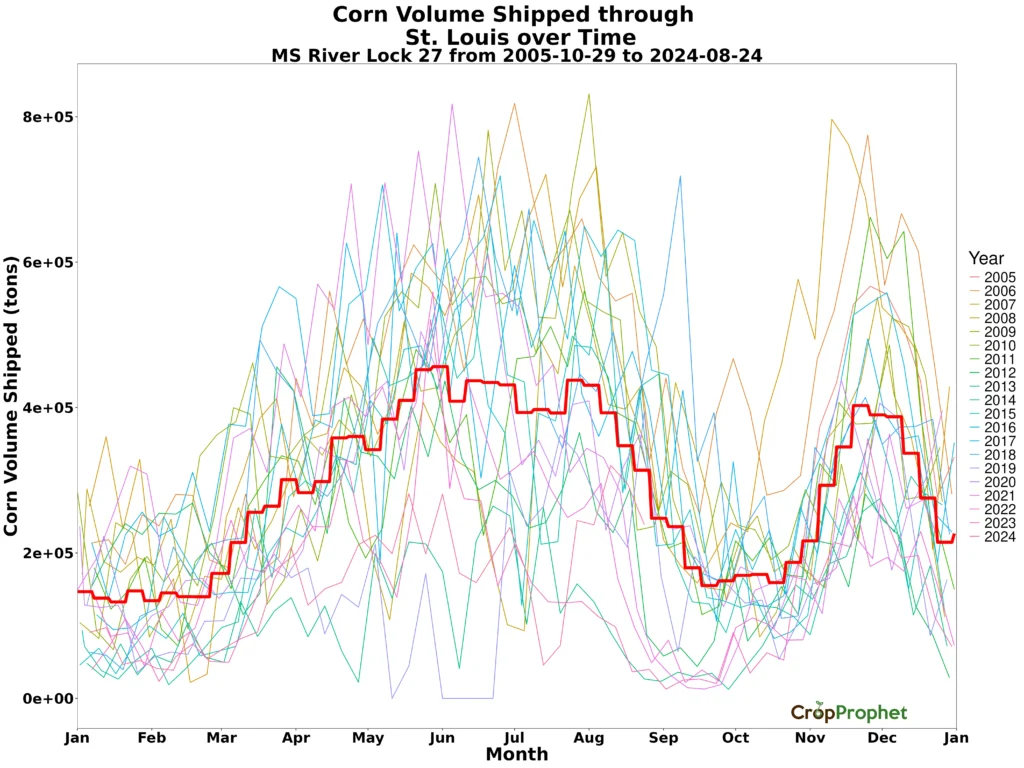

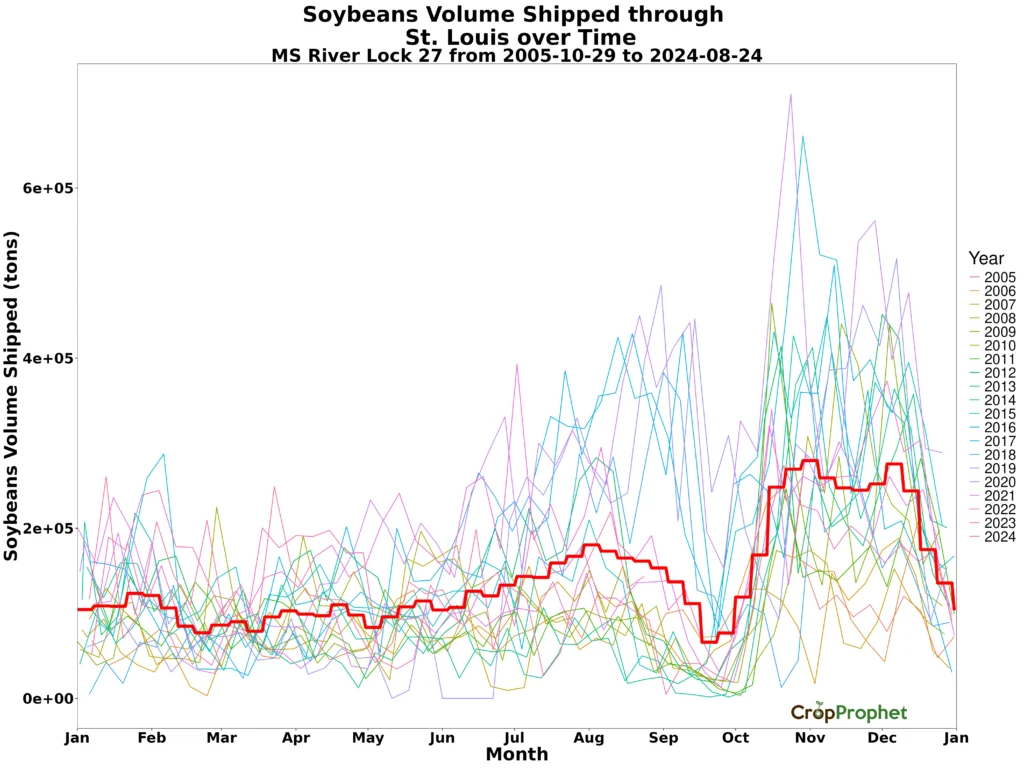

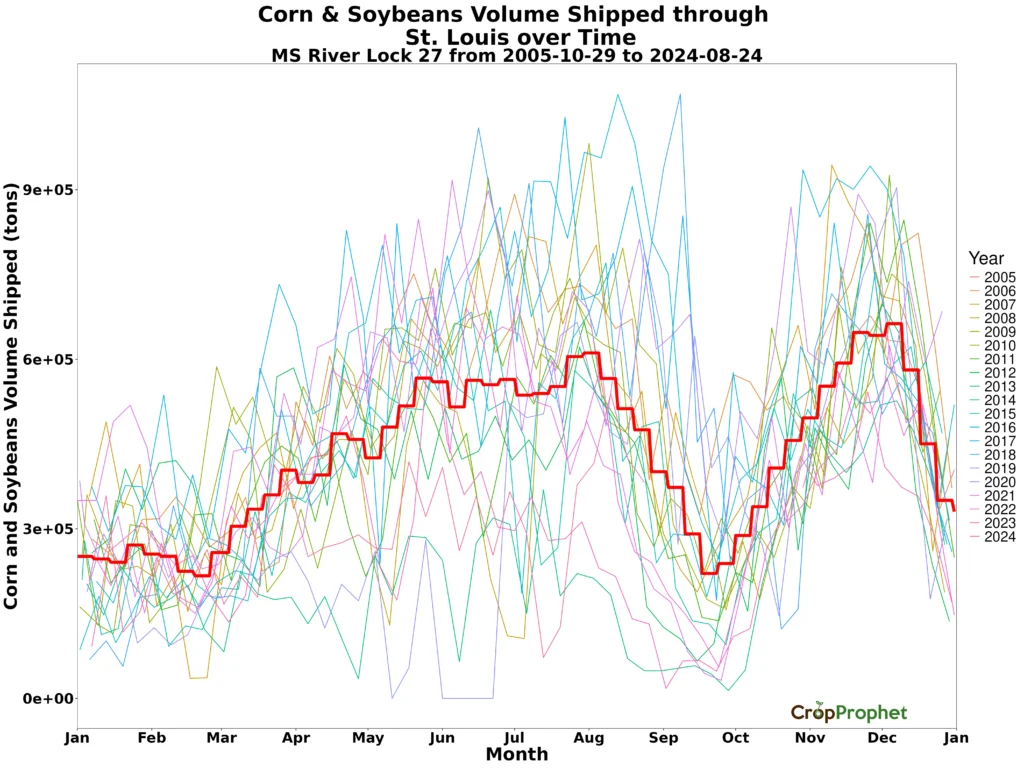

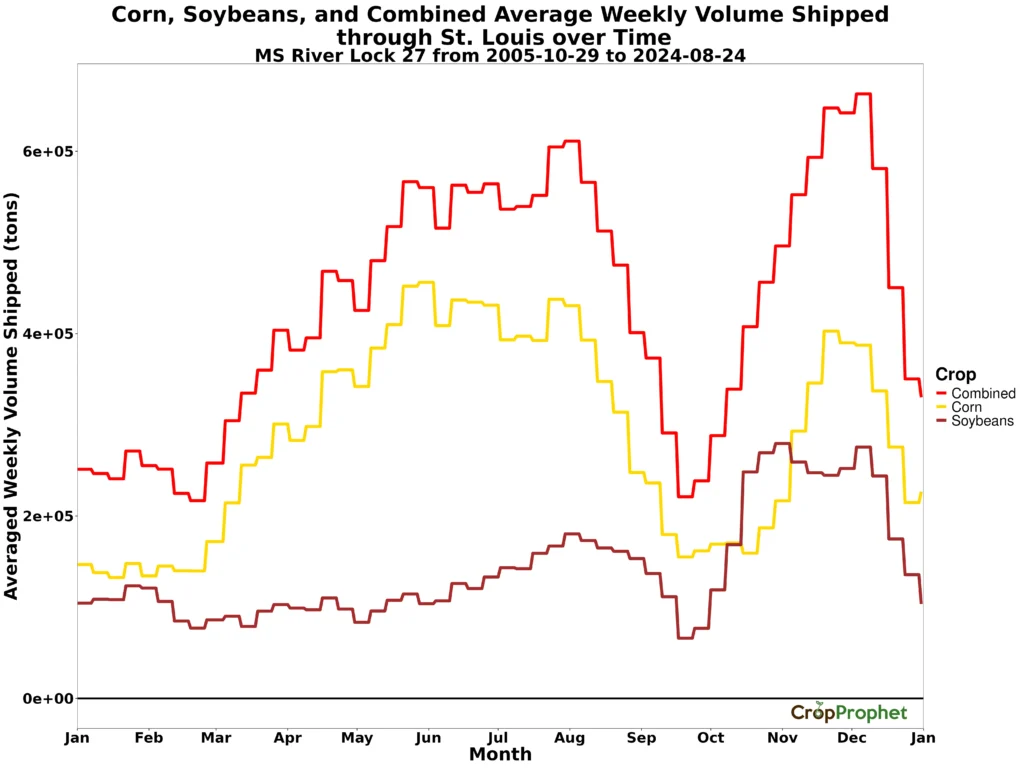

To account for seasonal trends, this analysis calculates both the weekly climatology and the weekly deviations from climatology. Figure 1, which shows the weekly volume of corn shipments from October 29, 2005, to August 24, 2024, illustrates a clear seasonal pattern in corn shipment volumes through St. Louis. Peak shipments typically occur from April to July, followed by a secondary peak between November and December. These trends are interspersed with periods of significantly lower shipment volumes.

Incorporating climatology is essential as it establishes a baseline for understanding recurring seasonal patterns. Without this context, an analysis based solely on raw shipment data could mask the underlying trends and fluctuations inherent to the shipping cycle. The analysis highlights predictable seasonal behaviors by including climatology, enabling a clearer distinction between normal seasonal variations and deviations driven by external factors like weather, market dynamics, or infrastructure challenges. This approach ensures a more nuanced and accurate interpretation of the data.

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Figure 1. (a) Corn volume shipped through St. Louis over time using Mississippi River lock 27. (b) Soybeans volume shipped through St. Louis over time using Mississippi River lock 27. (c) Corn and soybeans combined volume shipped through St. Louis over time using Mississippi River lock 27. (d) This visualization presents the average weekly shipping volume trends over time for corn, soybeans, and their combined total. The red lines in graphics (a), (b), and (c) represent these trends, highlighting seasonal patterns and variations for each category.

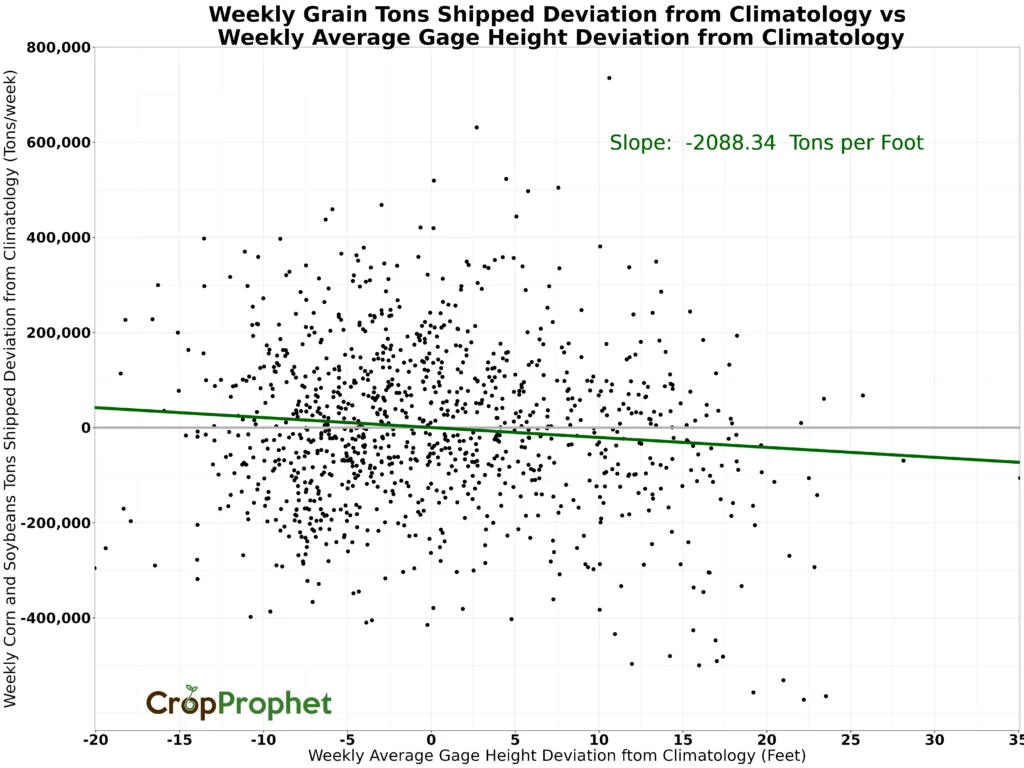

At the start of this analysis, we use a scatterplot to visualize the relationship between the weekly grain tonnage deviation from climatology and the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology, applying a linear regression method (Figure 2). The regression reveals a negative slope of -2,088.34 tons per foot, but a simple linear regression may not be the most appropriate analysis tool, in this case.

Figure 2. Linear regression of the weekly grain tons shipped deviation from climatology versus the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology.

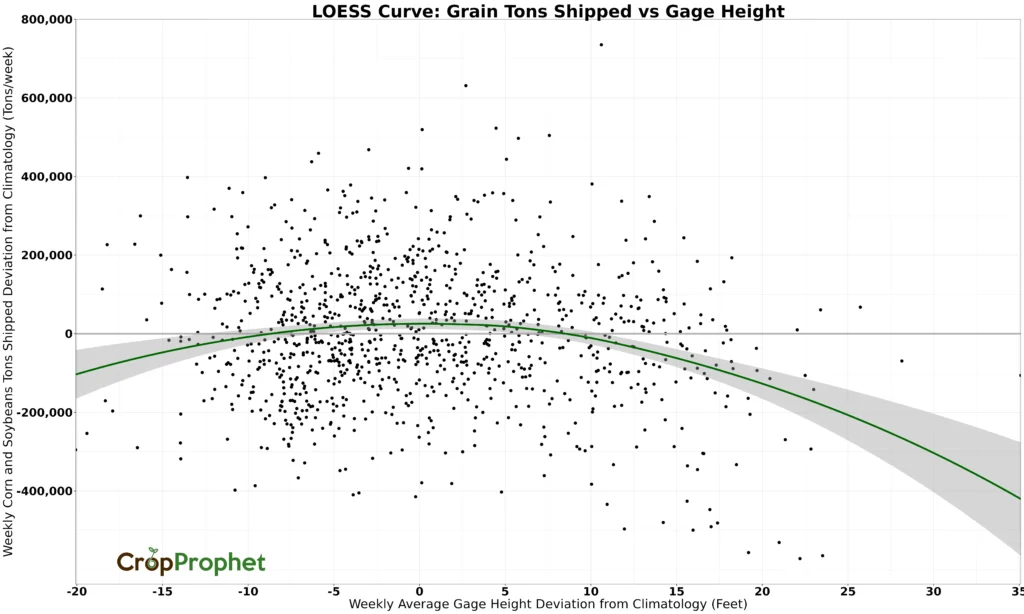

To further explore the relationship between Mississippi River height and grain shipment volume, we employ the Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing (LOESS) method. LOESS generates a smooth curve through the scatterplot by fitting multiple localized regressions to the data. Figure 3 illustrates the resulting LOESS curve, highlighting the non-linear relationship between weekly grain tonnage deviations and gage height deviations.

Figure 3. LOESS curve of the weekly grain tons shipped deviation from climatology versus the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology.

Mississippi River Grain Shipment Crtical Height: What is it?

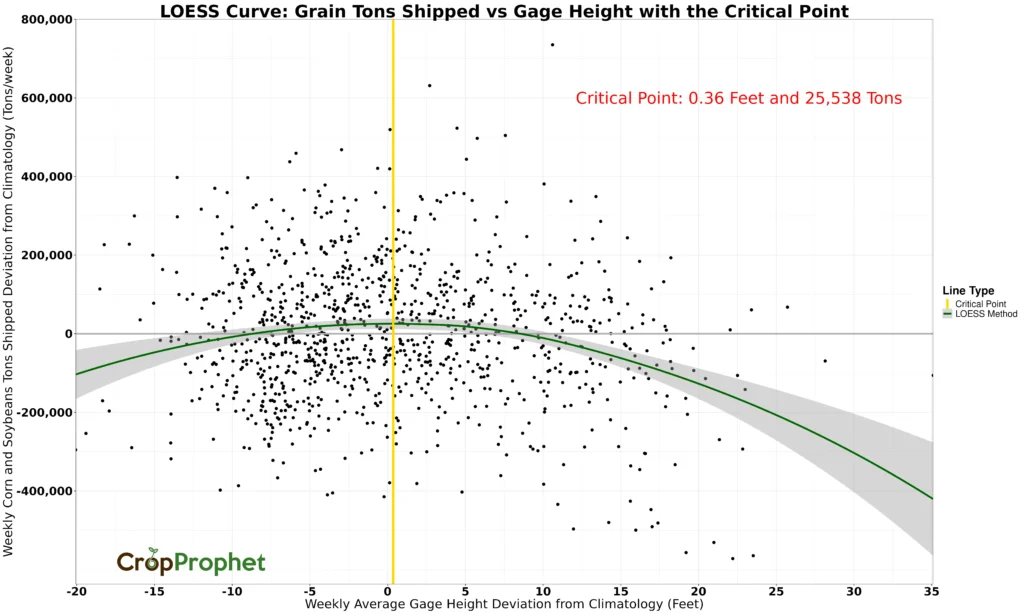

This analysis identifies a critical river height, which is the height at which grain volumes are maximized. Grain shipment volumes decline if the river heights increase or decrease from this level. This is demonstrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. LOESS curve of the weekly grain tons shipped deviation from climatology and the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology with the critical point.

Knowing the critical river height, we proceed to fit a linear regression line on either side of this value. The result is presented in Figure 5. To maintain continuity, the slopes are adjusted to converge at the same value at the critical point. All subsequent plots with slope calculations follow this approach to ensure consistent continuity.

Figure 5. Weekly grain tons shipped deviation from climatology versus the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology with kinked slopes at the critical point.

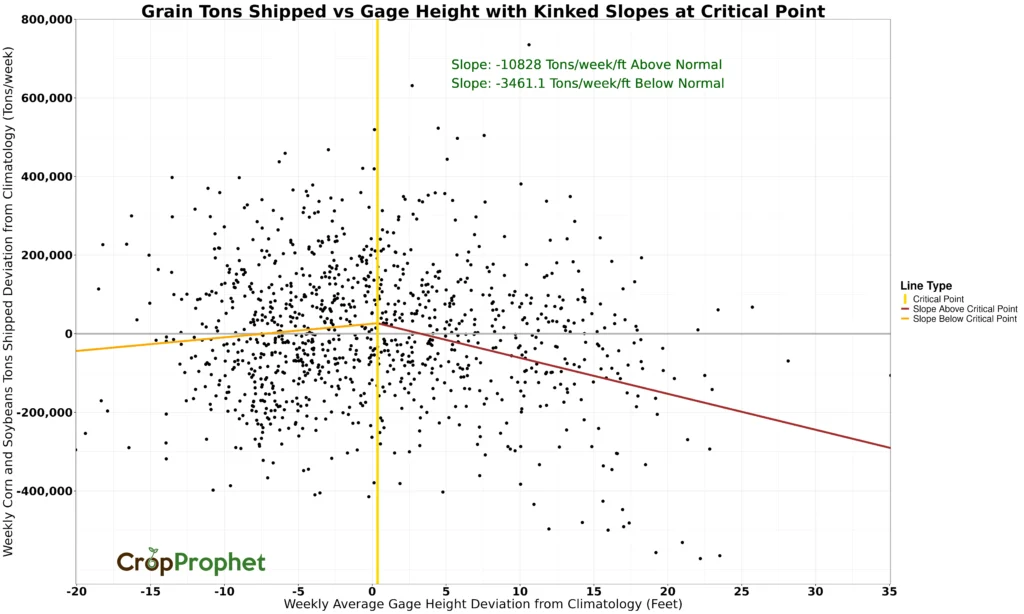

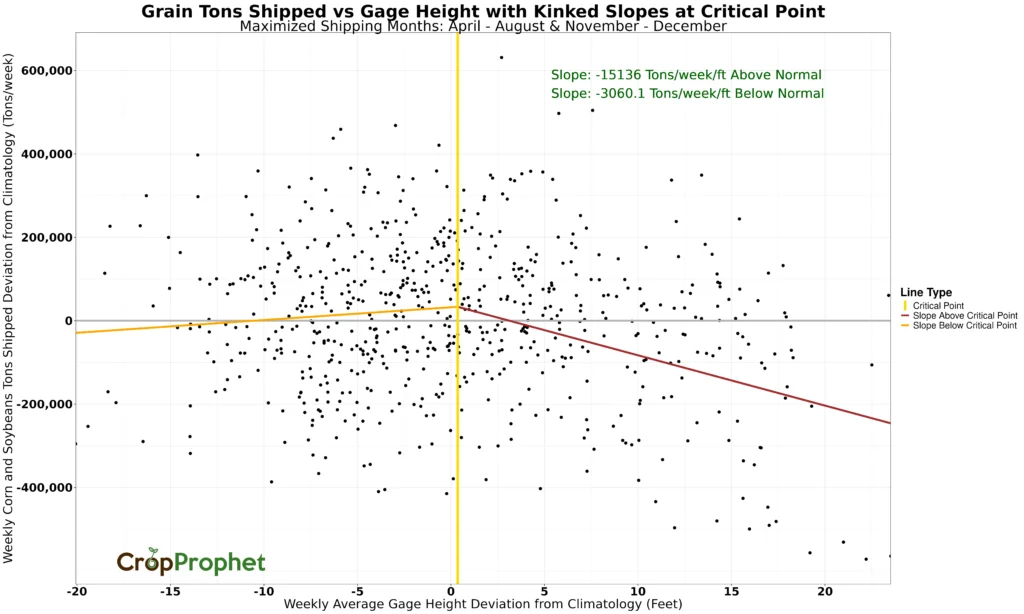

Figure 5 presents the results of the analysis for all weeks of the year. As discussed, there is a distinct annual cycle to weekly grain shipment volumes. Is the impact of river height on shipment volumes, measured by the slopes of regression lines, sensitive to this annual cycle?

To answer that question, the regression is performed again but for the maximum volume shipping months only. Based on the combined corn and soybean graphic (Figure 1-c), the peak shipping periods span from April through August and again from November through December. A visualization similar to Figure 5 is presented below, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Weekly grain (corn and soybeans) tons shipped deviation from climatology versus the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology during the maximized shipping months.

Corn and Soybeans Volume Shipped and Mississippi River Gage Height

The USDA downbound shipping data, which provides the number of grain barges per week, does not distinguish between corn, soybeans, and wheat. It classifies only “grain” barge counts.

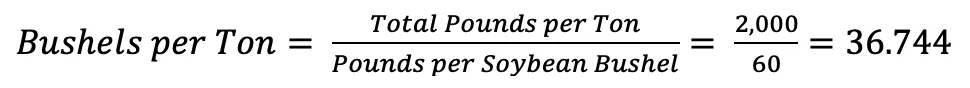

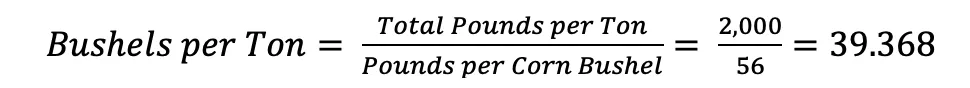

We assume all barges are carrying corn or soybeans and use corn and soybean standard weight conversions to convert tons shipped to bushels shipped. This allows us to compare our results to Mr. Steenhoek’s quote directly.

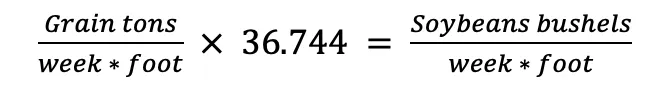

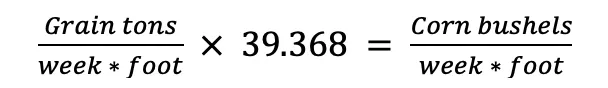

According to USDA standards, 1 ton equals 2,000 pounds, with 1 bushel of soybeans weighing 60 pounds and 1 bushel of corn weighing 56 pounds. Using these values, we calculate that 1 ton of soybeans is equivalent to 36.744 bushels (Equation 1), and 1 ton of corn is equivalent to 39.368 bushels (Equation 2).

Equation 1.

Equation 2.

Equation 3 demonstrates how the conversion factors from Equation 1 and Equation 2 are applied to transform grain (corn and soybeans) tons per week per foot into soybean bushels per week per foot. A similar approach is used for corn, as outlined in Equation 4. For this analysis, we assume that all grain data exclusively represents either soybeans or corn. This assumption aligns with the dominance of these two crops in USDA downbound grain shipping data for the regions analyzed. Using the conversion factors, we calculate that 1 ton equals 36.744 bushels of soybeans and 39.368 bushels of corn, enabling accurate conversion from tons to bushels for these crops.

Equation 3.

Equation 4.

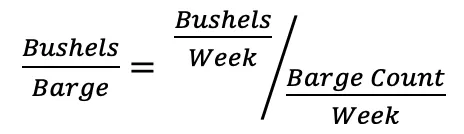

Before completing the full conversion, we first calculate the average number of weekly barges during the maximized shipping months. This is determined as the mean of all weekly values during these peak months, which results in an average of 347.82 barges per week, or approximately 50 barges per day. Once the data is converted into units of soybean bushels per week or corn bushels per week, we divide the bushels per week by the average number of weekly barges during the maximized shipping months, as outlined in Equation 5. This calculation is performed separately for both corn and soybeans.

Equation 5.

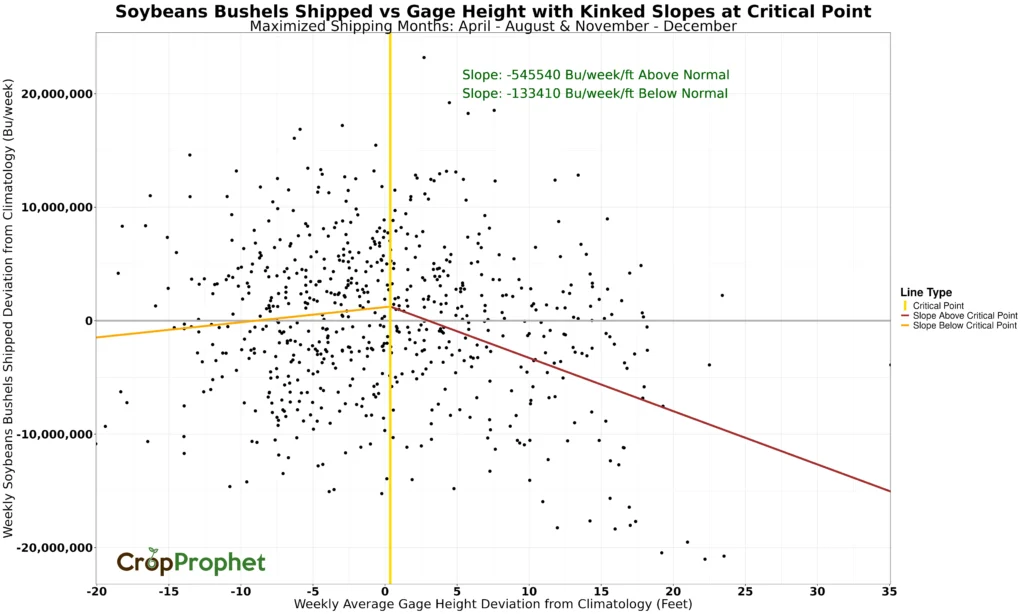

Next, this analysis visualizes the relationship between bushels per barge and the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology for both soybeans and corn, as shown in Figure 7. Consequently, the slope derived from this plot represents the rate of change in bushels per barge per foot of gage height deviation.

(a)

(b)

Figure 7. (a) Soybeans bushels shipped deviation from climatology per the average number of weekly barges versus the weekly gage height deviation from climatology during maximized shipping months. (b) Corn bushels shipped deviation from climatology per the average number of weekly barges versus the weekly gage height deviation from climatology during maximized shipping months.

Figure 7-a illustrates the slopes for soybeans both below and above the critical point. Below normal, the slope is -675.91 bushels per barge per foot, while above normal, it steepens to -1,709.2 bushels per barge per foot. Similarly, Figure 7-b presents the slopes for corn. Above the critical point, the slope is -1,831.3 bushels per barge per foot, whereas below normal, it is -724.18 bushels per barge per foot.

Mississippi River Level Grain Shipment Impact: Results

Our analysis shows the volume of grain shipments on the Mississippi River are impacted not only by low water levels, but also by high water levels (Figure 3). In fact, the high-water levels per foot above the reference height have a greater impact reducing grain shipments than the equivalent reduction in water levels.

Our analysis (Figure 4) also identifies the critical point—the weekly average gage height that maximizes grain shipments through the port, which is calculated to be 0.36 feet.

To verify the grain shipment impact mentioned in the quote (7,000 bushels per foot per barge), we examined the grain tons shipped deviation from climatology per week against the weekly average gage height deviation from climatology. This allowed us to calculate the slope of grain tons per week per foot for both below and above the critical point, as shown in Figure 6. Both slopes are negative, indicating reductions in grain shipping capacity as the river heights change from the critical height.

For below-normal values, as gage heights decrease further from the critical point (moving left toward more negative values), reduced water levels increasingly limit the volume of grain shipped. Conversely, as water levels approach normal, capacity improves. For above-normal values, the negative slope indicates that higher deviations from the critical point sharply reduce grain shipping capacity as gage heights increase. Notably, the slope above normal is much steeper in magnitude compared to the slope below normal, suggesting that high water levels have a more pronounced impact on Mississippi River grain shipping volume than very low water levels.

Following this analysis section and completing the unit conversion process, we arrive at a bushel of grain shipped per foot of river level in Figure 7. In this case, we limited the data to months demonstrating relatively high average shipment volumes. The resulting slopes align with the units specified in the opening quote (i.e. -7,000 bushels per foot per barge).

Our estimates of the impact of the Mississippi River on grain shipments are different than quoted. Figure 7-a shows that soybean shipping capacity decreases by 675.91 bushels per barge for each foot below normal and by 1,709.2 bushels per barge for each foot above normal. Like in Figure 6, both slopes are negative, meaning any deviation from the critical point reduces capacity. However, the impact of higher water levels is much greater, as shown by the steeper above-normal slope. Neither slope, however, matches the value mentioned in the opening quote. Table 1 summarizes the resulting slopes analyzed for both above-normal and below-normal conditions.

Impact of Mississippi River Heights at St. Louis on Grain Shipment Volumes

Table 1. Summary of the slopes calculated above and below the critical point for Figures 6, 7-a, and 7-b. The table highlights the impact of deviations from the critical point on grain shipping capacity, with separate analyses for grain tons (Figure 6), soybean bushels (Figure 7-a), and corn bushels (Figure 7-b). The slopes quantify the rate of change in shipping efficiency in relation to gage height deviations from climatology.

Conclusion

The findings in this analysis, illustrated in Figure 7-a and summarized in Table 1, reveal that the slope on both sides of the critical point diverges significantly from the value stated in the quote. This discrepancy underscores the complexity of grain shipping dynamics, where multiple factors influence the relationship between gage height deviations and Mississippi River shipping capacity.

The analysis highlights that deviations from the critical point—whether below or above normal—negatively affect grain shipping. However, the impact is notably more severe on the above-normal side of the critical point. Higher gage heights introduce greater operational challenges, including increased safety risks, infrastructure strain, and potential shutdowns. In contrast, lower gage heights, while still limiting capacity, allow for some operational adjustments, such as reduced draft levels. This distinction underscores the asymmetry in how high and low water levels influence barge efficiency.

Figure 6 and Figure 7 reinforce the conclusions from Figure 3 through Figure 5, demonstrating that high water levels present greater logistical and regulatory challenges compared to low water levels. Flooding, infrastructure damage, and safety risks associated with elevated gage heights are significantly more disruptive than the adjustments required for reduced water levels.

Looking forward, quantitative grain analysts and logistics planners can leverage tools like CropProphet for precipitation monitoring at the county level in the Upper Mississippi and Missouri River Basins. These tools can serve as an early warning system, enabling stakeholders to anticipate potential disruptions to Mississippi River grain shipments. By proactively identifying weather-driven risks, analysts can optimize shipment schedules, mitigate delays, and stay ahead of price fluctuations, ultimately enhancing supply chain resilience.

Works Cited

AGDAY TV. (2024, October 25). How drought’s grip on the Mississippi River is already costing farmers. AgWeb. https://www.agweb.com/news/business/taxes-and-finance/historically-low-river-levels-mississippi-river-are-already-costi

Engineers, U. S. A. C. of. (2025, January 2). Downbound barge grain movements (tons): Open AG Transport Data. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. https://agtransport.usda.gov/Barge/Downbound-Barge-Grain-Movements-Tons-/n4pw-9ygw/about_data

Engineers, U. S. A. C. of. (2025b, January 2). Upbound and downbound loaded and empty barge movements (count): Open AG Transport Data. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. https://agtransport.usda.gov/Barge/Upbound-and-Downbound-Loaded-and-Empty-Barge-Movem/w6ip-grsn/about_data

National Water Dashboard. USGS. (n.d.). https://dashboard.waterdata.usgs.gov/app/nwd/en/

Weights, measures, and conversion factors for Agricultural Commodities and Their Products. (n.d.). https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41880/33132_ah697_002.pdf